Spatial Localization in Older Adults with Single and Dual Sensory Impairment

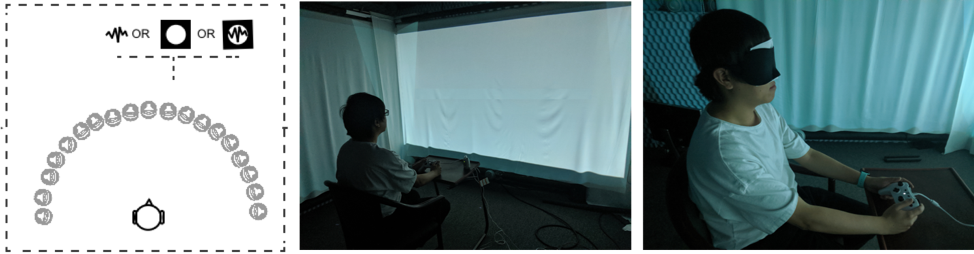

The ability to locate visual and auditory stimuli is important in many everyday tasks. While localization may be taken for granted in many healthy adults, many forms of sensory impairment result in difficulty localizing stimuli in the impaired modality. Diseases like macular degeneration, for example, can lead to missing stimuli in certain locations, and hearing loss can make it hard to accurately locate sounds of interest. Less well understood, however, is how sensory impairments affect localization of stimuli in other sensory modalities or of multisensory objects. For instance, does visual impairment prevent accurate localization of a car that can be both seen and heard, or can the sound of the car be used to compensate for poor visual localization? A group of researchers including Dr. Gordon Legge, Dr. Peggy Nelson, Dr. Yingzi Xiong, and graduate student Doug Addleman are addressing this and related questions with an audiovisual localization task conducted in CATSS in populations of older adults with hearing loss, visual field loss, and dual sensory loss.

Spatial localization is largely intact in healthy older adults.

A group of older subjects with normal vision and hearing had similar localization performance with a control group of young subjects. When localizing a multisensory object, the older and young groups utilized the same strategy, which was to primarily rely on vision. Interestingly, older subjects appeared to rely more on their visual sense even when localizing a purely auditory stimulus - they make more errors and were more uncertain about their responses when localizing sounds while blindfolded.

In addition to the impairments in localizing stimuli caused by sensory loss, dual sensory loss causes problems not seen in either vision loss or hearing loss alone.

Subjects with hearing loss made larger sound localization errors, and were more variable in their responses, compared to their age-matched peers with normal hearing. Subjects with vision loss were still fairly accurate in reporting the location of visual targets, but they became more variable in their responses as visual acuity deteriorates. Besides these deficits in vision and auditory localization, subjects with dual sensory loss also exhibited more “source confusions” - they showed larger discrepancies in their perceived locations of a sound and a light that essentially came from the same location.

Impaired vision is still valuable for facilitating auditory localization.

As in older subjects who had normal vision and hearing, subjects with sensory impairment also localized sounds better when they were not blindfolded. This encouraging finding indicates that despite reduced visual acuity, impaired vision is still valuable for distant tasks such as determining the whereabouts of sounds.

Ongoing projects

Inspired by these findings, the research team is conducting several projects to further explore the impacts of sensory impairment on spatial localization.

- Ongoing project 1: Extending current findings to real-life contexts. In collaboration with clinicians and occupational therapists, the research team is designing real-life localization tasks in residential areas.

- Ongoing project 2: Exploring the impact of the “source confusions” on social interactions. Do people with dual sensory loss, who exhibit such source confusions in lab tasks, “mismatch” the speaker and the voice when talking to multiple people in a real-world setting?

- By Yingzi Xiong and Doug Addleman